History of Indigenous Art

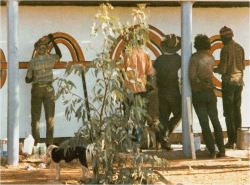

Fig. 1: School wall mural in Papunya, 1917, printed in: Bardon, Geoffrey and Bardon, James: Papunya. A Place Made After the Story. The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement, Melbourne 2004, p. 15

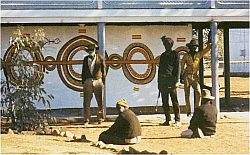

Fig. 2: School wall mural in Papunya, 1917, printed in: Bardon, Geoffrey and Bardon, James: Papunya. A Place Made After the Story. The Beginnings of the Western Desert Painting Movement, Melbourne 2004, p. 17

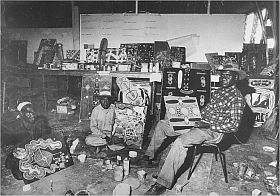

Fig. 3: "Men's Painting Room", Papunya 1972, printed in:

Benjamin, Roger and Weislogel, Andrew C. (eds.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings

from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell

University, New York 2009, p. 20

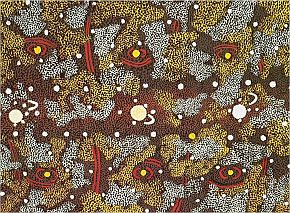

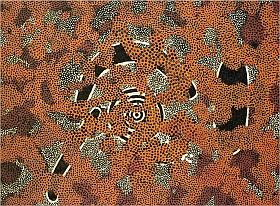

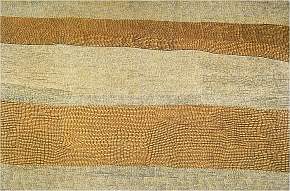

Fig. 4: (Detail) Tingari Tjukurrpa at Karrkurritinytja, by Simon Tjakamarra, 1986, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 214 x 274 cm, printed in: Art Gallery of Western Australia (ed.): Indigenous Art - Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth 2001, p. 37

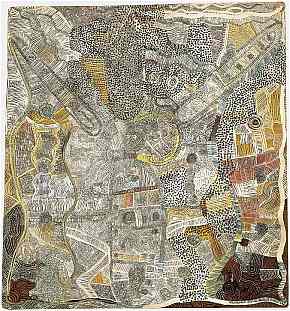

Fig. 5: (Detail) Ngalyilpi (A Small Snake), by Kaapa Tjampitjinpa 1972, synthetic polymer paint on wood, 121,9 x 95,3 cm, printed in: Benjamin, Roger and Weislogel, Andrew C. (eds.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, New York 2009, p. 140

Fig. 6: Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, Sun, Moon and Morning Star Tjukurrpa, 1973, synthetic polymer paint on wood, 45 x 58 cm, printed in: Bardon, Geoffrey: Papunya Tula. Art of the Western Desert, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne 1991, p. 121

Fig. 7: Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Sun Tjukurrpa, 1972, 43 x 58 cm, printed in: Bardon, Geoffrey: Papunya Tula. Art of the Western Desert, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne 1991, p. 116

Fig. 8: Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, Walter Tjukurrpa at Kalipinypa, 1972, synthetic polymer paint on wood, 80,7 x 75,6 cm, printed in: Benjamin, Roger and Weislogel, Andrew C. (eds.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, New York 2009, p. 126

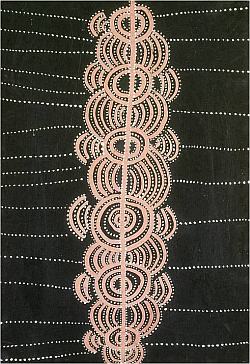

Fig. 9: Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, Yam Travelling in Sandhills, 1971, synthetic polymer paint on wood, 51,4 x 35,9 cm, printed in: Benjamin, Roger and Weislogel, Andrew C. (eds.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, New York 2009, p. 94

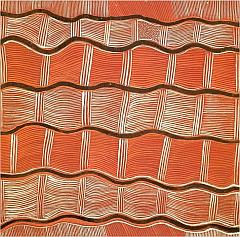

Fig. 10: Mick Namarari Tjapaltjari, Wind Tjukurrpa, ca. 1978, synthetic polymer paint on wood, 55 x 56 cm, printed in: Perkins, Hetti und Fink, Hannah. (ed.): Papunya Tula. Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney 2000, exh. cat., p. 41

Fig. 11: Mick Namarari Tjapaltjari, Tjunginpa, 1990, Acryl auf Leinwand, 122,5 x 182,5 cm, printed in: Benjamin, Roger und Weislogel, Andrew C. (ed.): Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, New York 2009, p. 168

Beginnings of the Contemporary

Indigenous Art Movement in Papunya

Flashback: The USA still celebrates the first moon landing; fear of the Cold War spreads across Europe; in Australia, the first Minister for Aboriginal Affairs is appointed and in Canberra the parliament argues about assimilation or self-determination for Indigenous people in Australia; in Alice Springs, in the heart of Australia and 2027 km distant from Canberra, the town counts its 10.000th inhabitant; in Papunya, 240 km northeast, a radio blares from a humpy.

A radio in a humpy? How on earth does a radio find its way into a shelter which is not much more than a wind break made from corrugated iron and bits of blanket? The answer to the puzzle: Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, an open-minded, bustling Indigenous artist, was famous on the Papunya reservation for his bartering. A radio for a painting. Or a leather jacket (useful in the cold winter nights in central Australia in July and August) for a painting. The enthusiastic art teacher Geoffrey Bardon happily gave up both items in return for paintings, which were worth at the time 75 to 100 Australian dollars and are today valued at up to 275.000 AUD. It was probably the first radio in a humpy in Australia. It was 1971.

Social and Political Conditions Offer a Way Out: Art

At the beginning of the 1970s, in Papunya, there was something like an outbreak of artistic activity - and Kaapa Tjampitjinpa was right in the middle of it - that would within only 15 years inspire many Indigenous artists across all Australia to actively develop their art. Today, Indigenous art is not only extremely various, it has become one of the most important aspects of art on the Australian scene. How this came about can only be understood using some basic knowledge of the political and social conditions of the times.

The South Australian and Northern Territory Aboriginal Protection Acts, enacted in 1910/11, permitted the establishment of reservations with internment of Indigenous people. The Chief Protector became legal guardian over all Indigenous children; marriage between Indigenous persons and whites was subject to ministerial approval.

In the 1920s and 1930s, there was a series of massacres of indigenous peoples, for example the infamous Coniston Massacre of 1928, whereby the perpetrators were acquitted in court. For Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, whose mother was murdered in the late 1920s in such a massacre, those years were known as “the killing times”.

During a conference held in 1937, concerning assimilation politics, a proposal was made: if one collected apart all “half-breeds”, the “full blood Aborigines” would become extinct within 50 years, and Australia would have solved a problem.

Towards the end of the 1960s, and particularly in the 1970s, the assimilation politics were reduced. It was, however, a long time before this became much apparent in Papunya, which was officially opened in 1960, or in other reservations.

When Geoffrey Bardon arrived in Papunya in 1971, as teacher at the local school, between 1000 and 1400 First Australians from four different language groups lived in the community. The Indigenous peoples, who were accustomed to traveling without restrictions across huge tracts of country, were cut off from their homelands, cut off from the very basis of their spiritual life.

There were continual problems with the food supply; diseases such as meningitis, hepatitis, syphilis, measles and encephalitis were horribly common. Many died, in particular small children. The personnel of the “hospital”, a run down corrugated iron shed, consisted of two nurses. Because the Indigenous inhabitants were not allowed to approach the houses of the whites at night, the nurses could not be called for emergencies. The little bodies were brought in the next morning.

At school, the children were forbidden to speak their own language. Patronization, humiliation and a pronounced racism by the white administration were endemic. The few members of the 75-strong white community who, like Bardon, built up contacts with the Indigenous inhabitants, were ostracized.

The School Walls

Bardon noticed that the Indigenous peoples used a form of pictography: curves, circles, meandering lines and animal tracks were drawn onto the sand. At school, however, the children painted only horses and stockmen. After a while, he hit upon the idea to ask some local people to decorate the school walls.

The older men, who worked at the school as caretakers or the like, agreed to the idea and painted on one of the walls three stories based on their oral histories: a Widow, a Wallaby and a Snake story. A short time later, Bardon received a visit from several of the eldest men in the community, who wanted to find out, what was going on at the school and who this strange teacher was?

Bardon passed this examination, obviously, because from then on the 45 year old Kaapa Tjampitjinpa (ca. 1926-1989) was appointed by the elders to supervise further painting of the school walls. Old Tom Onion Tjapangati gave permission to use as a theme the Tjukurrpa of the Honey Ant, one of the most important oral traditions of central Australia.

Around the same time in Papunya, in typical complete ignorance of the Indigenous culture, a sacred tree which was a local symbol of this important oral tradition was fenced off inside the newly-built compoud of the police station, making it totally inaccessible to the Indigenous people.

In June and August 1971, the artists Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Don Ellis Tjapanangka, Paddy Stewart Tjapaltjarri, Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri, Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra and Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula painted two different versions of the Honey Ant Tjukurrpa, which differed in the pictorial representation of the honey ants. In the first version, the honey ants were represented by arcs, however that version needed to be replaced since such a representation was considered too sacred to be publicly displayed.

In 1973, the paintings on the school walls were destroyed on behest of a new school administration, whitewashed over in an act of departmental vandalism. Yet those artworks nevertheless changed the reputation and the status of the Indigenous Australian artists across the entire Australian society. For the first time, the artists had made the life of the Indigenous Australians, their country, their culture, visible for all to see.

Beginnings of the New Art Movement

The paintings on the school walls caused a small revolution: the men realized that they could aspire to something extra, something in between the intense spiritual life in the desert and the sad, insignificant life on the reservation. Some began asking Bardon for art materials and were regularly to be found painting behind one of the classrooms. That was the beginning of the new art movement.

However, those beginnings were founded on still earlier events. Prior to the arrival of Geoffrey Bardon, Kaapa Tjampitjinpa and his cousins Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (c. 1932-2002) and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri (c. 1929-1984) (1) were already painting and carving objects destined for sale and not only for religious ceremonies. They knew Albert Namatjira (1902-1959), the first Indigenous artist to be renown across Australia (for his water colours) and thus had a good understanding of the concept of a (professional) artist.

In the early days, the men would use for their artworks whatever material was available...which was not much: hardboard, plywood or linoleum plates, poster and emulsion paints. With a few rare exceptions, access to canvas and synthetic polymer paints started only in 1973. Approximately 1,000 paintings were created by 39 artists in just two years from 1971 to 1973, mainly on wood.

Bardon encouraged everyone who wanted to paint to leave their jobs - if they had one -, because he could sell their artworks for them in Alice Springs for 75 to 100 AUD each, which was much more than they received in regular earnings. That made further enemies for Bardon, especially within the so-called Welfare Department, because it lost its workers, but in addition because the money earned with art showed that it was possible to become independent of government jobs and governmental direction. The local community administration even tried to prevent the art sales, with the argument that the artists were wards of the state and therefore the paintings were the property of the Crown.

Overcoming all hurdles, the artists' cooperative Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. was founded in November 1972 (2), with Kaapa Tjampitjinpa as its first chairman.

Sacred/Secret

Towards the end of 1972 in Yuendumu, on the occasion of a joint sports weekend, a small collection of artworks from Papunya was exhibited. A Pitjantjatjara man made vehement objections concerning one painting, however, which was thereaupon hurriedly removed from the exhibition. Dating from that incident, artists took care not to include sacred/secret symbols in their works: not only because of their own mores, but also because, in the traditions of the First Australians, it can be dangerous for strangers to observe sacred/secret symbols.

This reduction in symbolism led on the one hand to new visual styles, e.g. to a covering over and obscuring of the symbols, and on the other hand to the development of classical iconographies which served to identify (without use of sacred symbols) the more important Tjukurrpas. Thus the Tingari Tjukurrpa, an extremely important oral history associated with initiations, relating the creative acts of the ancestors during their journeys, is usually symbolized by a series of concentric circles, often joined by multiple straight lines. The Indigenous artists developed a new, more or less widespread, pictorial symbolism, which could unfold its impact on large canvases, as shown to particular effect in the adjacent painting by Simon Tjakamarra.

Today’s First Australians from the region near Papunya still find in those early artworks a deeper message than that which untutored eyes detect. Therefore, for example, the American collectors John and Barbara Wilkerson had their collection of early works from Papunya critically examined for dangerous symbology in 2009 by senior people from the relevant language groups, prior to allowing an exhibition and accompanying catalogue to be completed. The final decision was to exclude such works from the main catalogue and to allow the supplement to be sold only outside of Australia.

The artwork “Ngalyilpi (A Small Snake)”, painted in 1972 by Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, demarcates the initial stage of the new “safety first” consensus in the art movement. The colour palette is dramatically brighter, due to the white, compactly applied dots and short lines which overlay the symbols of the snakes. The snake figures are shown approaching and disappearing into their lairs under the sands of the spinifex country to the north of Yuendumu. This represents both the typical behaviour of snakes and also the actions of the ancestor figures. The dots representing spinifex grass are not uniformly painted, are indeed heaped closely together in some places, in order to differentiate them from other plants symbolized by oval-shaped groups of dots.

Cross-influence and Independence

Mutual influence between artists and other individuals is frequent and normal in the entire art world and is especially strong when the artists live and work so near to eachother as in Papunya. An example is found by comparing two paintings from Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri “Sun, Moon and Morning Star Tjukurrpa” (1973) and from Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri “Sun Tjukurrpa” (1972).

In the Indigenous culture, the sun represents a man, the moon a woman. In the paintings, an ancestor figure sits at a fireside behind a windbreak. In the painting by Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri, the irregularly dotted shapes represent clouds and a night scene. He describes a love story, and the journeys of sun and moon across the heavens are a part of their everlasting romance. The stars represent the campfires of warriors from the ancient past who had ascended into the heavens. The Morning Star is particularly important for the ceremonial dancers, who await the dawn.

The painting by Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri is likewise a love story, because the sun is also a metaphor for love. A man sings magically, to draw a young woman near; the older the man, the greater his spell’s potency, because with increasing age comes knowledge and power. The artistic technique produces the visual impression of sunlight, clouds, shadows and the red earth.

In both paintings, a strong multi-layered three-dimensional element is visible, as also seen in works by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula (c. 1918-2001), who developed from the beginning his own unique aesthetics. He was the first Indigenous artist to work with “dots”, which however were not small, circular and precise, but tended to consist of short strokes.

The painting “Water Tjukurrpa at Kalipinypa” is one of three water Tjukurrpas that Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula painted around August 1972, at a time when it rained incescently in his region. The artist was responsible for the area of Kalipinypa, which is why he was often inspired to paint it.

Kalipinypa is a holy site for storms, rain and/or water, and lies about 300 to 400 km west of Alice Springs. It is a huge flat claypan which, due to its geological character, stores runoff from rain like a sponge and contained a natural spring (which was however destroyed in recent times). Every feature of the landscape across that holy site, a kilometer in diameter, was (is) connected with the time of creation: certain sand dunes represent primordeal clouds, certain trees are associated with the storm birds “Kalwa”, some cliffs are associated with lightning, others with hail.

As in many early works painted at Papunya, artists portrayed various edible plants, in this case the solanum centrale, a low herbaceous plant, which especially thrives and produces berries when rain occurs after a bush fire. The berries dry up after some time and resemble raisins. The black points in the picture stand for the raisins, which are called Kampurrarpa (as is the bush). The associated country is at the mountain of the same name, Kalipinypa, which lies to the north at the Ehrenberg Ranges.

The symbols shown in the painting represent flowing water, or also the roots of the Kampurrarpa, or even Tjurungas and other secret objects, or caves and waterholes.

The country of Kalipinypa is divided in the painting into many parts, each visually distinct. There is an enormous variation in the techniques of overlayering: short, strong white lines, dotted with dark points in places, which allow the dark background to emerge in the form of fragile lines; parallel straight or curvaceous lines, sometimes connected by transverse strokes; crosshatching; dotted parallel arcs, etc. With few exceptions, light colours cover dark. The complexity of the themes portrayed correspond to the complexity of the pictorial execution.

Further Refinements, beyond Symbols

Even when artists and their paintings are associated with a particular part of country, i.e. with the country belonging to them or their parent(s), it is not obligatory that the pictorial representation be constrained to appropriate symbols handed down over generations. It was possible for individual forms of expression to develop, in contrast to the situation for ground paintings made for religious ceremonies, because the paintings were works by individuals.

Due to the above, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri (c. 1927-1998) could play a major role in raising the entire art scene at Papunya Tula to a new level, with his reduction in pictorial elements in the late 1980s and 1990s. However, one can already see experiments in that direction in earlier works.

In complete contrast to the works by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, the painting “Yam Travelling in Sandhills” from 1971 by Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri shows enormous simplicity. The artist succeeds in filling the entire canvas using a few lines of white dots. The visual emphasis is on the sand hills in the center, which is characteristic of the Yam Tjukurrpa. The straight track in the center leads through important sites represented by concentric circles. The larger arcs stand for sand hills, the smaller U-forms nearby represent women and children.

Mick Namarari Tjapaltjari was the first Indigenous artist who worked exclusively with lines. His artwork “Wind Tjukurrpa” from 1978 contains only a single small dotted area, undoubtably of special (although unrecounted) importance. The painting relates to a mythological wind, which is itself associated with the location Marnpi, the place of birth of the artist. The horizontal dark lines can again be interpreted as itineraries, in this case of the wind. Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri shows a rhythm of wind gusts and lulls using vertical lines, and enhances the flux in the painting by means of light-dark gradations and the finely coordinated colours for which he is renowned.

Similar remarks apply also to the painting in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, entitled “Tjunginpa” (or alternatively sometimes just “Untitled”). It relates to the story of the small marsupial mouse, whose tiny animal tracks are transformed into a perfectly balanced composition by the artist.

The painting is associated with the oral history of the hill “Tjunginpa”, northwest of Walungurru (Kintore), where Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri stayed until his death, after his years in Papunya. Walungurru is at the border between the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri was one of the first artists who experimented with artworks entirely of “dots”, without any symbols, a style which later inspired many artists in central Australia to experiment, to find new means to infuse structure into pulsating clouds of points.

Notes

(1) From the literature, it is not certain whether Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri were brothers.

(2) The meaning of the name Papunya Tula is not reported consistently in the literature. Bardon and Bardon (2004, P. 7) refer to “Honey Ant Meeting Place” whereas Bardon (1991, p.36), reports that the word Papunya refers to the smaller of two hills near Papunya, “Meeting Place for all Brothers and Cousins”.