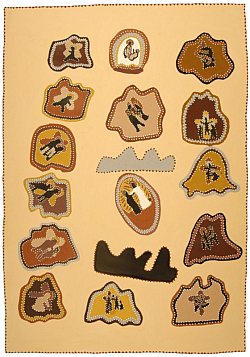

Plate 1: Shirley Purdie (*c. 1948), “Stations of the Cross,” 2007, natural ochre and pigments on canvas, 213 x 151 cm; printed in: Holleuffer, Henriette von and Wimmer, Adi (eds.): Australien. Realität - Klischee - Vision. Australia. Reality - Stereotype - Vision, Schriftenreihe im Auftrag der Gesellschaft für Australienstudien, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2012, p. 52

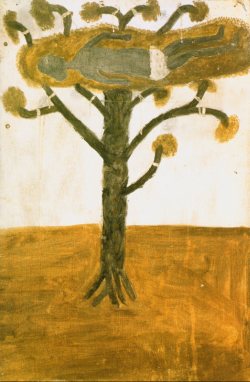

Plate 2: Hector Jandany (c. 1924-2006), “The Dead Christ in the Tree,” undated, natural ochre and pigments on canvas, 92 x 60 cm; printed in: Crumlin, R. and Knight A. (eds.), Aboriginal Art and Spirituality, Collins Dove, Melbourne 1991, p. 39

Plate 4: Matthew Gill Tjupurrula (*c. 1960), “Motherhood,” 1982, acrylic on canvas, 240 x 119 cm; printed in: Crumlin, R. and Knight A. (eds.), Aboriginal Art and Spirituality, Collins Dove, Melbourne 1991, p. 58

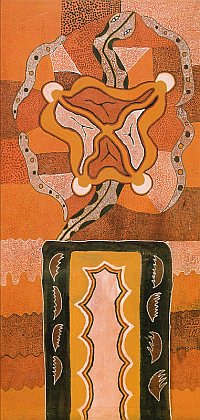

Plate 5: Clarise Nampijinpa Poulson (*1957), “Wapirra (Trinity),” 2002, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 80 cm; printed in: Holleuffer, Henriette von and Wimmer, Adi (Hg.): Australien. Realität - Klischee - Vision. Australia. Reality - Stereotype - Vision, Schriftenreihe im Auftrag der Gesellschaft für Australienstudien, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2012, p. 58

Plate 6: Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (ca. 1932-2002), Good Friday, 1994, acrylic on canvas, 116 x 154 cm; printed in: Johnson, Vivien, Clifford Possum, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 2003, p. 189

Plate 7: Lin Onus (1948-1996), “And on the Eighth Day…,” 1992, acrylic on canvas, 182 x 245 cm; printed in: Neale, Margo (ed.), Urban Dingo – The Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948-1996, Craftsman House, Brisbane 2000, p. 90

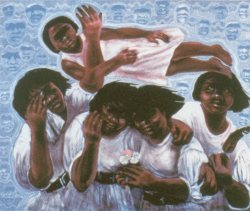

Plate 8: Julie Dowling (*1969), “A Welcome of Tears,” 1999, acrylic, red and white ochre and silver on canvas, 100 x 120 cm; printed in: Flinders University City Gallery (ed.), Holy, Holy, Holy, Flinders University City Gallery, Adelaide 2004, p. 60

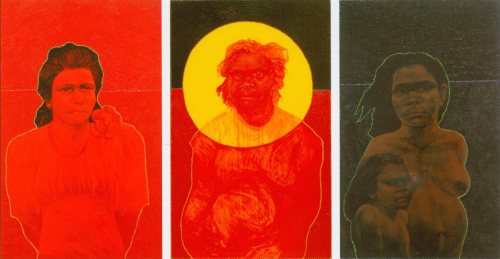

Plate 9: Julie Dowling (*1969), “Minority Rites I, II, III,” 2003, acrylic, blood, red ochre and plastic on canvas (triptych), 80 x 50 cm each; printed in: Flinders University City Gallery (ed.), Holy, Holy, Holy, Flinders University City Gallery, Adelaide 2004, p. 75

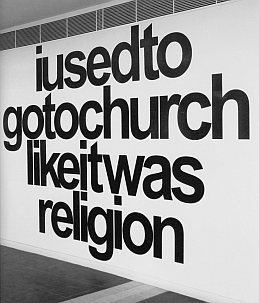

Plate 11: Vernon Ah Kee (*1967), “likeitwasreligion,” 2007, vinyl on wall (installed at Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney); printed in: Institute of Modern Art (ed.). Vernon Ah Kee: Born In This Skin, Brisbane 2009, p. 51

The Impact of Christianity

on Australian Indigenous Art

In 2007, Shirley Purdie won the Australian $ 15.000 Blake Prize for Religious Art with her painting “Stations of the Cross.” She was the first Indigenous artist to do so. Yet, when studying books on Indigenous art, one encounters a quite significant number of images concerning Christianity. What enables Indigenous artists to create paintings with Christian themes, even though one of the primary characteristics of Indigenous art lies in the narrative connection to the artist's country in its special Indigenous sense? What enables Indigenous people, who in their own views of religion include neither guilt nor original sin, to become involved with Christianity? What understanding or interpretation do the artists have of the Christian elements in their paintings? Are there differences between the works of artists who live in the larger cities and those who live in the outback? Some evidence and tentative answers for these questions compose this article.

The Genesis of a Belief in Two Ways

Since the landing of Captain Cook in Australia, it has been disputed whether the Indigenous inhabitants are capable of understanding Christianity. The Anglican minister Samuel Marsden stated for example in 1819:

“The Aborigines are the most degraded of the human race […] The time is not yet arrived for them to receive the great blessings of civilization and the knowledge of Christianity” (1).

Even in the 20th century there was a widespread belief, justified in a number of different ways by anthropologists, that Indigenous people could not be converted to the Christian faith. Baldwin Spencer, anthropologist at the University of Melbourne and for a few weeks in 1911 Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Northern Territory, believed that Christianity was destructive to the Indigenous Australians, because they could not understand it (2). Another view of anthropologists was that Indigenous people already possessed a comprehensive and satisfying religion, so that there was absolutely no internal necessity to adopt other beliefs. Aram Yengoyan, anthropologist at the University of California, went even further and tried to prove, using the example of the Pitjantjatjara people, that a religious conversion was impossible, because their beliefs were diametrically opposed to those of Christianity (3).

Within the Indigenous concept of country certain physical places are inseparably connected with spiritual practice. At these sites, where ceremonies were and are performed, the human world connects with that of the ancestors. Lynne Hume, Associate Professor at the School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics at the University of Queensland, maintained that no Christian church or shrine could possibly generate the spiritual power associated by Indigenous people with specific sacred sites or with country (4). Indeed, a further argument could be that the Indigenous view of country as a living entity, which can be injured and feel suffering, and which must be nurtured, contradicts Christian teachings that land is to be used, cultivated, exploited, in a word: subjugated. Indigenous beliefs do not incorporate an eternal struggle between good and evil; the ancestors are not associated just with the good, but combine both characteristics, exactly as do humans. That humans are mortal is not a consequence of original sin.

The Indigenous religions seem divergent or even disjunctive. Nevertheless, it is a fact that many Indigenous people avow belief in a Christian God. How did this come to be?

The history of prosyletism and the varied approach of the missionaries, from a partial preservation of the Indigenous culture through to a harsh suppression, are described elsewhere (5). The missions were in the beginning largely unsuccessful for a variety of reasons. (6) Some failed simply because of the unusual and difficult economic conditions in the desert. Many missions – until 1928 there were more than 100 (7) – were abandoned, because the ongoing violence by the white settlers against the Indigenous inhabitants precluded development of a trusting relationship toward the missionaries. It took a long time for the missionaries to see the necessity of learning the local languages or learning about the Indigenous culture. Their goal was always – and this is the important point – to replace that culture with a Christian one.

The missionaries worked particularly with children. It was very difficult to convert the elders because they were the most experienced in their religion and law. The children were separated from their parents, so that the parental influence and the transmission of Indigenous knowledge could be broken. Even so, in the 14 years after the establishment of the local mission in Ntaria (Hermannsburg) in 1877, for example, only 25 mainly young Arrernte were baptized (8). That relative lack of success in prosyletism has changed fundamentally only in the last few decades. The essential factor has been the training of more and more Indigenous ministers who took over the parish churches.

The two examples of fundamental Indigenous beliefs, that of the creator ancestors and that of the meaning of country, serve to show how they have gradually been given a Christian perspective.

In the end of the 1990s, some Indigenous Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran and Uniting Church clergyman from Queensland developed an approach which they called Rainbow Spirit Theology:

We accept that God has spoken and continues to speak through the Christian Scriptures. This God of the Scriptures is known to Aboriginal people as the Creation Spirit, who speaks to us through the land. The land is like the Scriptures – sacred stories and signs are inscribed on the landscape, and readily available to those who can read them. (9)

The creator ancestors are not considered as separate entities, but as manifestations of one God, despite the well-known association of every Indigenous individual with specific creator spirits. The key aspect of this theology is to establish a connection between the Indigenous culture and Christianity:

“In this Theology, we seek to redeem this profound symbol [the Rainbow Spirit] and fill it with new meaning in the light of the Gospel” (10).

The previously mentioned difference between the Indigenous care for country, and the Christian subjugation of land, is resolved simply by using an alternative translation of the Hebraic biblical text (11).

The reactions of the Indigenous Australians to the Christian religion were and remain various, ranging from “We tried to become like white men, but found we couldn't. Our law was too strong” (12) to: “We believe in the old law and we want to keep it: and we believe in the Bible too. So we have selected the good laws from both and put them together” (13). Living according to both sets of convictions is called Two Ways and is visible in the artworks discussed next.

Contemporary Indigenous Art:

Interpretation in Two Ways – Case Studies

Shirley Purdie lives in Warmun, a community in the Kimberley in the northwest of Australia. There are strong Catholic influences, but Indigenous ceremonies are still commonly practiced. Many of the elders are simultaneously lawmen and Christians. “Stations of the Cross” does not follow the official sequence of fourteen scenes from the crucifixion, but begins instead in the upper centre of the picture with the birth of Jesus, continues with scenes anti-clockwise and ends below the first station with a 15th scene.

The western mode of representing the Stations of the Cross as separate and isolated images clearly influenced the composition of this work. Indigenous art portraying a number of sacred sites often uses a set of lines joining the sites to represent the journey of the creation spirits. Such lines are entirely absent here and the stations stand out prominently from the background. The figures of Jesus, the cross, et cetera are inset into outlined shapes which represent the nearby hills of the Kimberley. Thus, the country itself is as intrinsic to the painting as the life of Jesus; even without considering that the whole painting is itself painted with earth pigments, a part of the country.

This presence of country is further emphasized by the fact that Shirley Purdie includes in the painting two hills, in the same style as in nearly all her works. Together with the outlines of the Kimberley they incorporate the Indigenous aspect of Two Ways. The artist makes a subtle distinction between both kinds of hills by using grey and black colors for the latter ones. In this way, the painting portrays a balance between Christian history and the Indigenous meaning of country.

Another

means of expressing the relationship between Christian and

Indigenous religion is shown in the painting by Hector Jandany,

who likewise lives in Warmun and has painted since 1979. That

year saw the establishment of the Bough Shed School by two

Catholic nuns, invited in by the community. Hector Jandany lived

according to and in harmony with both religions. His painting

shows the body of Jesus, which lies on a platform in a tree. The

artist references thereby a traditional funeral ceremony in his

area. Note that the painting does not involve Christian

iconography. The artist is renowned for his subdued

color-palette in mostly dark tones. The fact that half of the

painting is filled with bright ochre helps to emphasize the bier

with the figure in black, the black Christ. The painting carries

the title “The Dead Christ in the Tree.” Hector Jandany painted

this work of art for the Easter service, for which it was used

in the church at Warmun for a number of years.

Another

means of expressing the relationship between Christian and

Indigenous religion is shown in the painting by Hector Jandany,

who likewise lives in Warmun and has painted since 1979. That

year saw the establishment of the Bough Shed School by two

Catholic nuns, invited in by the community. Hector Jandany lived

according to and in harmony with both religions. His painting

shows the body of Jesus, which lies on a platform in a tree. The

artist references thereby a traditional funeral ceremony in his

area. Note that the painting does not involve Christian

iconography. The artist is renowned for his subdued

color-palette in mostly dark tones. The fact that half of the

painting is filled with bright ochre helps to emphasize the bier

with the figure in black, the black Christ. The painting carries

the title “The Dead Christ in the Tree.” Hector Jandany painted

this work of art for the Easter service, for which it was used

in the church at Warmun for a number of years.

Also

interesting is a painting by Matthew Gill Tjupurrula, who began

painting in his early 20s at Wirrimanu (Balgo Hills). He created

many works for the church and the local school. The painting

entitled “Motherhood” from 1982 belongs to his early works for

the church, where it is still displayed. (14) The artist

emphasized the physical side of maternity by illustrating the

uterus, in complete contrast to the usual sanitized ideal of the

Virgin Mary. The snakes in the upper part of the painting are

neither a symbol for temptation in the Christian sense nor for

evil, but reference an Indigenous sacred symbol. Matthew Gill

Tjupurrula, like Hector Jandany, completely abstained from

Christian symbols in his painting yet nevertheless intended it

as ecclesiastical art.

Also

interesting is a painting by Matthew Gill Tjupurrula, who began

painting in his early 20s at Wirrimanu (Balgo Hills). He created

many works for the church and the local school. The painting

entitled “Motherhood” from 1982 belongs to his early works for

the church, where it is still displayed. (14) The artist

emphasized the physical side of maternity by illustrating the

uterus, in complete contrast to the usual sanitized ideal of the

Virgin Mary. The snakes in the upper part of the painting are

neither a symbol for temptation in the Christian sense nor for

evil, but reference an Indigenous sacred symbol. Matthew Gill

Tjupurrula, like Hector Jandany, completely abstained from

Christian symbols in his painting yet nevertheless intended it

as ecclesiastical art.

A further example, which also avoids Christian symbolism, is by Clarise Nampijinpa Poulson. It is entitled “Wapirra (Trinity)” and was painted in 2002.

The artist is a spokeswoman of the Warlpiri. She also follows both religions: her Indigenous beliefs and those of the Baptists who established a mission in Yuendumu in 1947.

Her work of art contains, from top to bottom, the following Wapirra (Trinity) Jukurrpa. As usual in the iconography used at Yuendumu, humans are represented by U-forms. Inside the brown, nearly closed arc at the top of the painting are people who live outside of the community of Christ, people who are not yet filled by the Holy Spirit. In the left center of the painting are three more U-forms; these people have begun to turn toward the Christian faith. The nearly closed circle at the bottom of the painting shows the same people as at the top, now filled by the spirit of God and living in Wapirra into all eternity. The Holy Trinity of Father, Son and the Holy Spirit is represented in the form of three brown semi-circles in the middle right part of the painting. (15)

Some

examples should now be given of paintings with explicit

Christian iconography. Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri painted only

this single work of art with a Christian motif, as far as my

researches sh ow. The artist, who was initiated at Napperby, but

also baptized in the Lutheran religion in Ntaria (Hermannsburg),

revitalized his Christian faith prior to a risky eye operation

in 1994; the other eye had been blind since his youth. In his

work “Good Friday,” which he painted during Easter in the same

year, he included the Christian iconography of the three

crosses. A crown of thorns is shown at the lower left, between

two of the crosses. Three oversized nails complete the Christian

symbolism. The three footprints, which lead to the cross of

Jesus, are often found in the works of Clifford Possum

Tjapaltjarri.

ow. The artist, who was initiated at Napperby, but

also baptized in the Lutheran religion in Ntaria (Hermannsburg),

revitalized his Christian faith prior to a risky eye operation

in 1994; the other eye had been blind since his youth. In his

work “Good Friday,” which he painted during Easter in the same

year, he included the Christian iconography of the three

crosses. A crown of thorns is shown at the lower left, between

two of the crosses. Three oversized nails complete the Christian

symbolism. The three footprints, which lead to the cross of

Jesus, are often found in the works of Clifford Possum

Tjapaltjarri.

The artist painted the background of dotted irregular fields in his characteristic style, which had already emerged in his earliest works of the 1970s. The background reminds one of clouds and shadows. In fact, however, the diagonal white and particularly orange-dotted areas represent the Milky Way. The lightning depicts the wrath of God over the death of His son.

Important for the current discussion are the seven concentric circles, Indigenous symbols for the Seven Sisters seen in the heavens as the Pleiades constellation which are painted in the same color as the crosses and the crown of thorns. The entire painting roils with the grey and red sky, a red which reminds more of Jesus' blood than of the Australian landscape. Thus we find united in this work Indigenous and Christian symbolism, equally juxtaposed.

Lin

Onus painted in a completely different style a similarly

dramatic sky in his 1992 painting, entitled “And on the Eighth

Day…” The artist had begun as a landscape painter. He lived in

Melbourne, belonging on the paternal side to the Yorta Yorta,

and on the maternal side ‘to Glasgow’ where his mother was born.

His father has been an Indigenous political activist in South

Australia, since the 1930s. Lin Onus visited Maningrida in 1986

as a member of the Australian Arts Board and met Jack Wunuwun

together with other important artists of northern Australia. He

was later initiated in Oenpelli, which he counted as one of the

most important events in his life (16). The intensive contact to

Jack Wunuwun and John Bulun Bulun crucially changed his

landscape painting, both in technique and in content. No longer

simple landscapes, his works of art carried intense messages.

Lin

Onus painted in a completely different style a similarly

dramatic sky in his 1992 painting, entitled “And on the Eighth

Day…” The artist had begun as a landscape painter. He lived in

Melbourne, belonging on the paternal side to the Yorta Yorta,

and on the maternal side ‘to Glasgow’ where his mother was born.

His father has been an Indigenous political activist in South

Australia, since the 1930s. Lin Onus visited Maningrida in 1986

as a member of the Australian Arts Board and met Jack Wunuwun

together with other important artists of northern Australia. He

was later initiated in Oenpelli, which he counted as one of the

most important events in his life (16). The intensive contact to

Jack Wunuwun and John Bulun Bulun crucially changed his

landscape painting, both in technique and in content. No longer

simple landscapes, his works of art carried intense messages.

In this work from 1992, Lin Onus inserted and interlaced iconic concentric circles into a realistic view of a typical thinly vegetated Australian bush scene. The artist thus portrayed the intimate Indigenous relationship to country, referencing country as a source of identity, as a cultural archive, country which is not to be disturbed or destroyed. Two angels fly across the Indigenous landscape, wrapped in the British flag. They are not the angels of deliverance but of death. For Lin Onus, the colours of the flag represent the colours of death, which he also used in his art installation from 1990 about the British atomic bomb test site “Maralinga”. The angels carry in their hands the symbols of the British invasion: a pistol as symbol for genocide, a sheep with barbed wire as a sign for destruction of the land, a Bible as indication of cultural destruction and a plastic bottle, which for Lin Onus was the paramount wasteful rubbish of the whites (17).

The artist uses the title of the painting “And on the Eighth Day…”, which immediately arouses associations of the creation history, and Christian symbols – the angels, the Bible – to criticize the invaders and their treatment of his country and people.

The

great portraitist Julie Dowling, influenced by confrontations

which her family had with Christian institutions, often deals in

her art with the brutal conditions in many missions. Her

painting “A Welcome of Tears” from 1999 depicts the inhuman

treatment of Indigenous girls in the St Joseph's mission at

Subiaco, a suburb of Perth. The story was handed down by Julie

Dowling's grandmother. The artist portrays her great-aunt and

grandmother as children together with other Indigenous girls,

who had been remanded to the mission orphanage. They perform a

funeral ceremony for one of their close friends, who died of

pneumonia, caused by starvation, hard work, and exhaustion. (18)

The

great portraitist Julie Dowling, influenced by confrontations

which her family had with Christian institutions, often deals in

her art with the brutal conditions in many missions. Her

painting “A Welcome of Tears” from 1999 depicts the inhuman

treatment of Indigenous girls in the St Joseph's mission at

Subiaco, a suburb of Perth. The story was handed down by Julie

Dowling's grandmother. The artist portrays her great-aunt and

grandmother as children together with other Indigenous girls,

who had been remanded to the mission orphanage. They perform a

funeral ceremony for one of their close friends, who died of

pneumonia, caused by starvation, hard work, and exhaustion. (18)

Note that the artist chooses the same position for the deceased child as Hector Jandany did in his painting “The Dead Christ in the Tree.” It is a depiction connected with funeral ceremonies in northern Australia. Thus, Julie Dowling does not select a Christian symbol to criticize the mission like Lin Onus did, but contrasts it with an Indigenous one.

In her triptych “Minority Rites I, II, III” from 2003, Julie Dowling portrays three women from three generations of her family, who were dominated by the power of the Church. Besides the persons and the Indigenous flag, the paintings contain many significant symbols, embedded in the backgrounds.

In the two paintings on the right side, the dotted horizontal line separates the sky from the Indigenous country, characterized by concentric circles. The sky in the painting on the right contains many Christian crosses. In the sky of the middle painting, the contour of the sun, which is used in the Indigenous flag, is repetitively drawn in fine lines. The sky of the painting on the left contains, inside a circle around the head of the woman, symbols for the country as well as hands which reach for Indigenous symbols for water. Underneath the symbols for water are several crosses. Julie Dowling uses in these paintings both Indigenous and Christian symbolism.

Julie Dowling explains the biographical and historical background:

I wanted to also illustrate the tensions, which have existed between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cultures regarding the use of religion as a colonizing tool. I also wanted to reflect on the history of forced removal and the tug of war between religions to get Indigenous souls to convert within Western Australia. My great grandmother, Mary Latham was taken from her mother Melbin who was ‘saved’ from the bush and was baptized in the Church of England. Melbin's daughter, Mary Oliver was taken from her and baptized Anglican. Mary Oliver's daughter, May Latham was also taken from her mother and she was subsequently baptized Catholic. This took less than 40 years to achieve. (19)

Vernon

Ah Kee is particularly known for his finely drawn portraits of

family members and friends, for video installations, and for

works of art, which use language and typography. The viewer has

to concentrate hard on his paintings, because of the artist's

use of kerning. This leads to a certain delayed, but more

powerful, impression.

Vernon

Ah Kee is particularly known for his finely drawn portraits of

family members and friends, for video installations, and for

works of art, which use language and typography. The viewer has

to concentrate hard on his paintings, because of the artist's

use of kerning. This leads to a certain delayed, but more

powerful, impression.

The artist often criticizes exclusion and racism in relation to the Indigenous population, in a sharp manner, and undermines the usual understanding of text and language.

In the work discussed here, however, Vernon Ah Kee manipulates language in a very ironic way with multiple connotations which show that he might not himself adhere to the Christian faith. It reads “i used to go to church like it was religion”. Readers automatically focus on the common-place idiom “do something religiously” meaning “frequently and with fervor”, but then double-take on the word “church” which connotes dutiful staid morality. Then viewers double-take again when they realize that is how the idiom actually arose – and the doubt flickers, whether the artist really meant it so? Then the word “used,” indicating past tense, is noticed on the second reading and viewers really contemplate going to church regularly, without really thinking of any alternative, then gradually breaking away from that until finally one would look back and smile sardonically about the past. Alternatively, there may be a double entendre, based on “I used to” indicating that now the person no longer attends church unthinkingly, but with intense conviction of the whole heart and mind. In this way, like in a haiku poem, the viewer is led through a gamut of impressions.

Acknowledgement: The above text is an abridged version of a similar article by the author in: Holleuffer, Henrietta, Wimmer, Adi (eds.), Australien. Realität - Klischee - Vision. Australia. Reality - Stereotype - Vision Series on behalf of the Association for Australian Studies, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2012, p.49-67, ISBN 9783868214079

Notes

(1) Cited in: May, John D'Arcy (2003). Transcendence and Violence: The Encounter of Buddhist, Christian, and Primal Traditions. New York, London: Continuum, p. 27

(2) Harris, John (1994). One Blood: 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity: A Story of Hope. Sutherland, NSW: Albatross Books, p. 404

(3) Yengoyan, Aram A. (1993). “Religion, Morality, and Prophetic Traditions: Conversion among the Pitjantjatjara of Central Australia.” Robert W. Hefner, ed. Conversion to Christianity: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives on a Great Transformation. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, p. 234

(4) Ranger, Terence (2005). “Christianity and the First Peoples: Some Second Thoughts.” Peggy Brock, ed. Indigenous Peoples and Religious Change. Leiden, Boston: Brill, p. 19

(5)

Austin-Broos, Diane J. (2003). “The Meaning of Pepe: God's

Law and the Western Arrernte.” Journal of Religious History

27.3, 311-28.

Brock, Peggy, ed. (2005). Indigenous Peoples and Religious Change. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Dewar, Mickey (2005). “You in Your Small Corner: The Love Song of Alfred J. Dyer: Early Days of Church Mission Society Missions to the Aborigines of Arnhem Land.” Humanities Research XII.1, 27-40.

Lake, Meredith (2008). ‘Such Spiritual Acres’ – Protestantism, the Land and the Colonisation of Australia, 1788-1850. University of Sydney, Ph D Thesis.

Loos, Noel (2007). White Christ Black Cross: The Emergence of a Black Church. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

McDonald, Heather (2001). Blood, Bones and Sprit: Aboriginal Christianity in an East Kimberley Town. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Morphy, Howard (2005). “Mutual Conversion? The Methodist Church and the Yolngu, with Particular Reference to Yirrkala.” Humanities Research XII.1, 41-53.

Pattel-Gray, Anne (1998). The Great White Flood: Racism in Australia. Critically Appraised from an Aboriginal Historico-Theological Viewpoint. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

Schwarz, Carolyn, and Francoise Dussart (2010). “Christianity in Aboriginal Australia Revisited.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 21. 1, 1-13.

(6) With some Indigenous groups, missionaries never had success in their evangelism. For example, Lutherans set up mission stations several times between 1887 and the 1980s for the Kuku-Yalanji group in northern Queensland, but there was no significant influence on their beliefs (Anderson, Chris (2010). “Was god ever a ‘boss’ at Wujal Wujal? Lutherans and Kuku-Yalanji: A socio-historical analysis.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 21.1, 33-50).

(7) Winter, Joan G., ed. (2002). Native Title Business: Contemporary Indigenous Art. A National Travelling Exhibition. Southport, Qld.: Keearia Press, p. 51

(8) Harris, John (1994). One Blood: 200 years of Aboriginal encounter with Christianity: A Story of Hope. Sutherland, NSW: Albatross Books, p. 399

(9) (The) Rainbow Spirit Elders ([1997] 2000). Rainbow Spirit Theology: Towards an Australian Aboriginal Theology. East Melbourne, Vic.: Harper Collins, p. 20

(10) ibid., p. 14

(11) ibid., p. 75

(12) Flinders University City Gallery, ed. (2004). Holy, Holy, Holy. Adelaide: Flinders University City Gallery, p. 12

(13) Berndt, Ronald M. (1962). An Adjustment Movement in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory of Australia. Paris: Mouton, p. 60

(14) Personal communication with Annette Cock, of Warlayirti Artists, Wirrimanu (Balgo Hills).

(15) Personal communication with Cecilia Alfonso, of Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation, Yuendumu.

(16) Leslie, Donna (2008). Aboriginal Art – Creativity and Assimilation. Melbourne: Macmillan, p. 248

(17) Flinders University City Gallery, ed. (2004). Holy, Holy, Holy. Adelaide: Flinders University City Gallery, p. 62

(18) ibid.

(19) ibid., p. 74