Fig. 1: Ochre Pits, central Australia

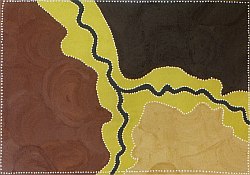

Fig. 2: Churchill Cann (Yoonany) (born ca. 1947), 1999, Texas Downs Country, ochre pigments on canvas, 100 x 140 cm, printed in: Aboriginal Art Galerie Bähr, Speyer, Kulturabteilung Bayer, Leverkusen, and Bayer Australia, Sydney (eds.): Das Verborgene im Sichtbaren. The Unseen in Scene, Speyer 2000, exh. cat., cover and p. 49

Fig. 3: Nancy Naninurra (born. ca. 1933), Yarllalya, 2000, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 118,5 x 79,5 cm, printed in: Aboriginal Art Galerie Bähr, Speyer, (ed.): Das Verborgene im Sichtbaren. The Unseen in Scene, 2. Aufl., Speyer 2002, exh. cat., S. 104

Fig. 4: Lin Onus (1948-1996), Barmah Forest, 1994, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 183 x 244 cm, printed in: Neale, Margo (ed.): Urban Dingo - The Art and Life of Lin Onus 1948-1996, Queensland Art Gallery, Craftsman House, Brisbane 2000, exh. cat., p. 76

Land and "Landscapes"

In the small community of Warmun, in the Kimberley, in the northwest of Australia, live a number of artists who have a fervent preference for painting with ochre pigments on canvas.

In the small community of Warmun, in the Kimberley, in the northwest of Australia, live a number of artists who have a fervent preference for painting with ochre pigments on canvas.

Ochre pigments have been used by First Australians since time immemorial, in ancient Rock Paintings and also in body painting for religious ceremonies which remain a part of the living culture. They have been extracted from the same locations for thousands of years (see e.g. the accompanying photo) and have been an item of cross-group trade across thousands of kilometers.

The artworks from Warmun represent in the first instance landscapes and often contain representations of local mountains, rivers, cliffs and caves, especially from areas in which the artists lived and worked in the past, e.g. on the station properties as cattle drovers or domestic staff. The painting by Churchill Cann (Yoonany) with the title “Texas Downs Country” is an example, whereby Churchill Cann (Yoonany) worked on the Texas Downs station property as a stockman.

The painting portrays a landscape as seen from above, with a river course winding through hills. One can imagine, when viewing this and similar paintings, that one views something like a topographic map, without any attempt at painting to scale. That is, elements of the landscape are generally represented in the appropriate directions from eachother, but not with distances in proportion.

The painting portrays a landscape as seen from above, with a river course winding through hills. One can imagine, when viewing this and similar paintings, that one views something like a topographic map, without any attempt at painting to scale. That is, elements of the landscape are generally represented in the appropriate directions from eachother, but not with distances in proportion.

Relationships between Paintings and Landscape

The adjacent photo - although from another area - shows clearly a visual relationship between paintings and landscape. That does not, however, imply that the painting belongs to the genre Landscape Painting as known in European art. The Indigenous artists portray neither idealised panoramas nor accurate, realistic reproductions of specific scenes. Even in the case of the famous watercolour artworks by artists from Ntaria (Hermannsburg), of whom Albert Namatjira is the most extraordinary representative, the artworks are not concerned with a faithfully exact illustration of a certain landscape. Rather, the paintings always embody the innate importance which country – with its relations to Creation, to the laws and mores of the First Australians and to material and spiritual resources – represents for the Indigenous peoples.

The illustration of country in the form of an aerial view is a frequent phenomenon in the art of the First Australians. It is also not unusual for the same painting to contain several different viewpoints, i.e. both aerial and side views, which is yet another indication that a faithful illustration of the landscape is not the artist's goal. Furthermore, the paintings almost never show use of perspective.

Pictorial Representation of the Unseen

This special aspect of “landscape painting” is not limited to works in ochre pigments. It can be found across the entire range of Indigenous art, as shown by the painting “Yarllalya” by Nancy Naninurra.

The painting represents an area of the country which belongs to the father of the artist and which lies south of Wirrimanu (Balgo) in the Great Sandy Desert. The meandering black lines show a riverbed in this area. Along the river, between small hills -  represented here as U-shapes - a pond developed, recognizable in the center of the painting as a long black shape. The smaller concentric circles represent trees which are typical for this area, whereas the main part of the painting shows sand dunes, which characterize this country.

represented here as U-shapes - a pond developed, recognizable in the center of the painting as a long black shape. The smaller concentric circles represent trees which are typical for this area, whereas the main part of the painting shows sand dunes, which characterize this country.

In this painting, and particularly in the skewed representation of river and pond, it can be recognized that simply copying an image of the landscape or simply showing specific characteristic details of the landscape is not the intention, but rather that here - as always - a pictorial translation or visual transformation takes place, with all its artistic freedoms.

It is not a case of simply reproducing what is visible, but rather the most important aspects of this type of painting are the meanings standing behind the objects, the spirituality embued in the country. One sees in fact two elements in these paintings: On the one hand, a certain visualization of the country, on the other hand the spiritual aspects embodied by it.

“Landscape Painting” in so-called Urban Art

Even the “Landscape Paintings” of Indigenous artists who live and work in the main cities in Australia experience a shift in meaning, whenever the artists confront their heritage. An example is provided by artworks of Lin Onus (1948-1996), who began his career using landscape styles strongly influenced by European modes. He lived in Melbourne, belonged on the paternal side to the Yorta Yorta, whereas his mother was born in Glasgow. His father had been an Indigenous political activist in South Australia since the 1930s, but that had not initially visibly influenced the art of Lin Onus.

Only as he took up intensive contact with artists from Arnhem Land, in particular with Jack Wunuwun and John Bulun Bulun, and after he had been accepted into their clan, did his landscape painting undergo crucial changes concerning the content. No longer just simple illustrations of landscapes, his artworks began communicating calculated purpose and meaning.

The painting shows a river landscape of the Murray River, its calm beauty broken by extracted jigsaw puzzle pieces. Yet on closer inspection it is clear that the pieces cannot be inserted back into the painting. The motif of the jigsaw puzzle, with its inherent optical illusion, is used by Lin Onus in many of his artworks to symbolize the fractures in Australian history, the fight for identity and the destruction of the environment. Only two years before creating this painting, with which the Artist won the renowned National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award in 1994, Lin Onus had learned that the Barmah National Park is a part of the country which belonged to him as his spiritual homeland, as part of his heritage.

The painting shows a river landscape of the Murray River, its calm beauty broken by extracted jigsaw puzzle pieces. Yet on closer inspection it is clear that the pieces cannot be inserted back into the painting. The motif of the jigsaw puzzle, with its inherent optical illusion, is used by Lin Onus in many of his artworks to symbolize the fractures in Australian history, the fight for identity and the destruction of the environment. Only two years before creating this painting, with which the Artist won the renowned National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Award in 1994, Lin Onus had learned that the Barmah National Park is a part of the country which belonged to him as his spiritual homeland, as part of his heritage.